The last segment of Alfa Museum’s permanent exhibitions focuses on speed and illustrates the exceptional racing pedigree of the Italian brand from several epochs. Alfa reached the top spot in many racing series from pre-war Grand Prix through Formula 1 down to modern touring cars, like DTM. In fact, Alfa did not just secure a top spot, but with cars like the P3 or the Alfetta, also holds records in dominating these series (most notably, winning every single Grand Prix in the 1950 F1 season).

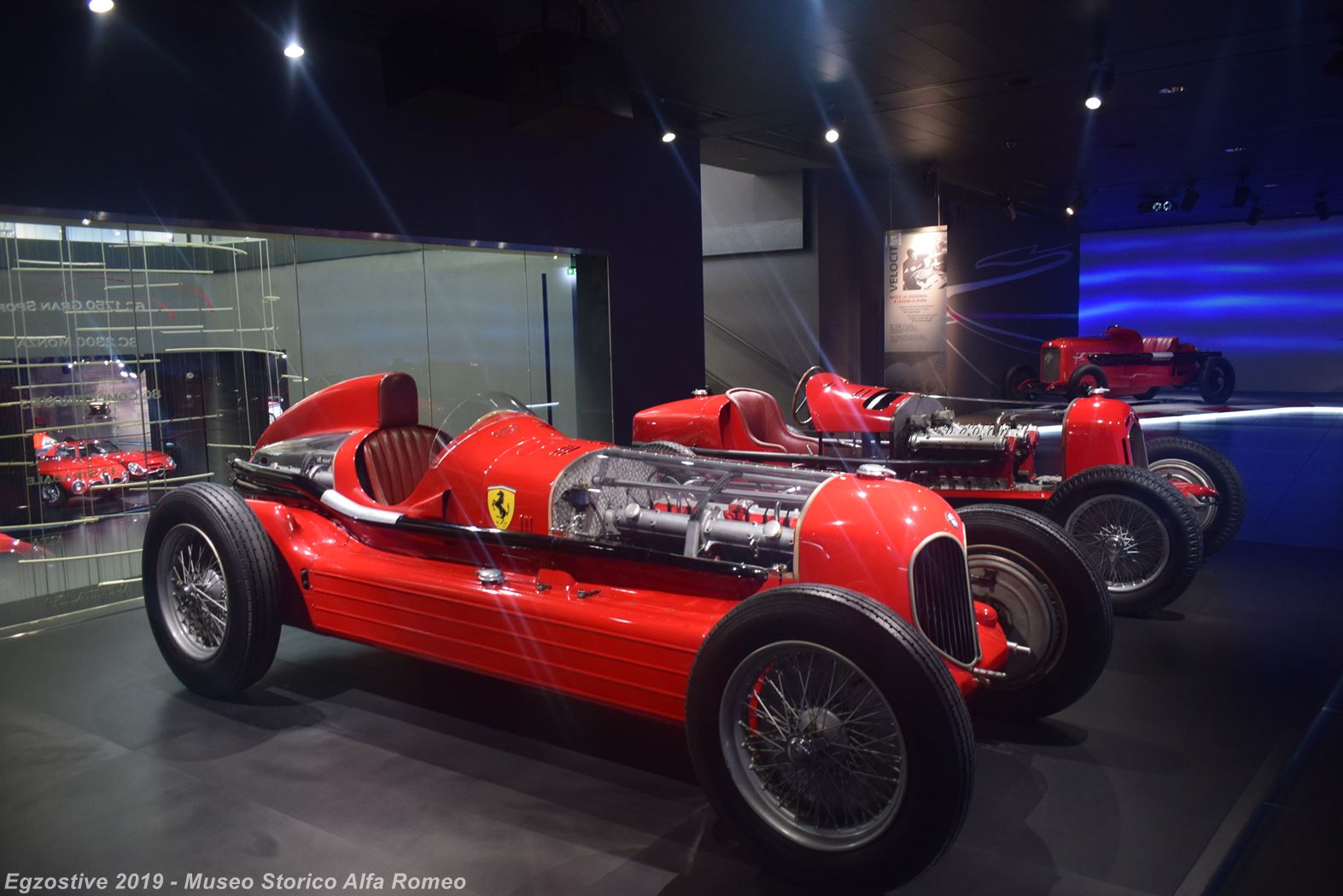

Upon arrival from the design exhibition upstairs, the Velocity segment welcomes with a jaw-dropping race car, the Alfa Romeo SF48 Bimotore from 1935 accompanied by a Tipo A race car.

The Bimotore is one of the most spectacular race cars of the pre-war period (or pretty much ever), even if born out of sheer desperation. These years marked the domination of Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union Grand Prix cars, made possible by the unlimited state financing.

Alfa Romeo assigned Scuderia Ferrari to build their own supercar under the new Formula Libre – effectively lifting all weight and power restrictions. The Bimotore was based on the Tipo B, but featuring 2 Tipo B engines of 3165 cc that were placed in front and behind the driver with the rear engine facing towards the rear.

The performance with 540 HP from the two engines was enormous and surpassed both Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union. The Bimotore was intended for the fast tracks of the Formula Libre calendar, and two Bimotore race cars were entered for the 1935 Tripoli Grand Prix with Nuvolari and Chiron behind the steering wheel. In the end, Nuvolari could claim fourth followed by Chiron in a race won by Caracciola. Two weeks later at the Avus Race in Berlin, Chiron conquered second place after Nuvolari did not finish due to constant shredding of his tires. In June 1935 Nuvolari set a land speed record on the Firenze-Lucca highway, his top speed on the second run exceeding 362 kilometres per hour. Ultimately, the Bimotore concept did not prove to be successful, as the breath-taking performance in a straight line came at the high price of high weight (1300 kg), delicate handling with tire-shredding. This latter took its tolls in frequent pit stops, as well as excessive fuel consumption. One of the two Bimotores was scrapped, the only remaining one was showcased at Lukas Hüni’s stage at this year’s Retromobile.

Lukas Hüni honoured the 110th anniversary of Alfa Romeo at Rétromobile

The Bimotore is accompanied by a Tipo A, the indirect predecessor of the Bimotore. This car from the early 30s could not account for a racing success comparable to its successors but illustrates well the evolution between the two extremes.

The two cars are surrounded by a selection of race cars with a cinematic show that provides the audio-visual background.

The first car with a cloverleaf is an Alfa Romeo RLTF (RL stands for the model, TF for Targa Florio).

This car was the race version of the RL road car, weighing almost half of the road versions, with a refined engine.

This car was the first one to use the green cloverleaf symbol on a white background. When Ugo Sivocci won Targa Florio in 1923, the emblem was carried on by the Alfa team for the sake of good luck.

There are a few exciting pre-war specimens, like the Tipo P2, that scored many with victories with Ascari behind the wheel.

The 6C 1500 Super Sport featured as compressor already in the late ‘20s.

My other favourite from this segment was an Alfa 8C 2900 B Speciale Tipo Le Mans from 1938. The 8C is a pre-war racing icon, scoring exceptionally well at auctions these days, and this model is one of the most exclusive and impressive variants. True to its name, it is powered by a 2.9 litre supercharged straight 8 producing 220 HP.

The beautiful aluminium bodywork was constructed by Carozzeria Touring and was among the very few closed cabin cars when almost exclusively open cars raced at Le Mans. The construction compensated well for the extra sheets of metal, and the welded tubular frame chassis justified the Superleggera name. The vehicle was entered the 1938 Le Mans 24 hour race, and also took the lead by a whopping margin of about 150 km before it retired.

The next segment commemorates the dominance of the Alfetta race cars during the earliest years of what we know today as Formula 1. The Alfa Romeo 158/159 (a.k.a. as the little Alfa), is a Grand Prix racing car using pre-war grand Prix racing technology best adapted to the new formula.

The unrivalled technology was also paired with drivers like Nino Farina, Juan Manuel Fangio and Luigi Fagioli. They were poets with the steering wheel. It also helped that, the competitors were not entirely out of the post-war shock or other crisis, see, e.g. the newborn Scuderia Ferrari using Jaguar engines.

Thanks to these lucky combinations of favourable factors, the Alfettas count among the most successful racing cars ever produced. In fact, the 158 and its derivative, the 159, took 47 wins from 54 Grands Prix entered and had a perfect year in 1950.

Accordingly, the Museo features both 158 and 159, also with the body panels removed to give access to the entire mechanics.

This segment also features a wall of fame with an endless list of championship titles.

The next stage features a legendary Tipo 33 Stradale, one of the sexiest sportscars pf the ‘60s, also spawning a series of exciting concepts presented in the previous article.

This car is a derivative of the Autodelta Tipo 33 sports prototype, which is also showcased just two corners further. True to the race car platform, the Stradale follows a mid-engined layout and is often credited as the world’s first supercar (it arrived the same year as the Miura). The sumptuous curvy design was created by Franco Scaglione and certainly matched the impressive specs.

The next stage features a 6C 3000 CM from the ‘50s. As the name suggests, the car uses a 6C engine, with considerable modifications. The CM designation stands for Competizione Maggiorata referring to the Enlarged Displacement for Competition purposes.

The 3.5-litre engine was paired with a tube frame chassis, with only six examples built. A coupé driven by Juan Manuel Fangio and Giulio Sala finished second overall at the 1953 Mille Miglia. Another car was handed to Pininfarina to showcase various design concepts in the following years.

The next car on the podium was a 1965 Alfa TZ2. Equipped with a fibreglass body, a mere 12 original models were built. The sophisticated technology brought class victories to Arese at dozens of races.

The next stage features two Formula 1 cars with massive spoilers, illustrating the vast developments the sport went through in just two decades since the departure of the Alfettas.

The red Formula One racer is a Brabham BT45, designed by South African engineer Gordon Murray for the 1976 Formula One season. In upgraded BT45B and BT45C form, it also competed in the 1977 and 1978 seasons. Alfa’s flat 12-cylinder engine even served the first year of the next Brabham design in the 1979 season.

This car was also showcased at the FCA Heritage stage of last year’s Techno Classica.

Foreign brands to challenge the Germans at the Techno Classica

The results were not so spectacular in comparison to the Alfettas, but it was a major venture, with Alfa committing itself for several years attracting Italian sponsors and great drivers. At the same time, the results can be considered underwhelming, given the flashy Italian sponsorship coming from Martini and Parmalat and world champion pilots like Lauda, Picquet, or vice-champion Reuteman.

The other F1 car is a Tipo 179F Test Car, symbolising the third entry of the brand into F1, albeit with lesser success. The first car was constructed by Alfa Romeo’s racing department Autodelta and featured Alfa Romeo flat-12 engine designed by Carlo Chiti for sports cars. The team evolved into a fully-fledged factory team from 1980 onward, and since 1976 the engine was supplied to Brabham until 1979. This team laid the foundations for the Benetton team that rose to fame a decade later.

The last car of the podium the 155-V6-TI represents the last golden age of Alfa racing efforts. The 155 V6 TI raced from 1993 to 1996 in the Deutsche Tourenwagen Meisterschaft and the subsequent International Touring Car Championship with notable success.

The FIA Class 1 Touring Cars were no holds barred racing beasts, the Group B of touring car racing. The Alfa threw all the right ingredients into the mix: the 2.5 L V6 engine was coupled to a four-wheel-drive system, producing 426 PS at a whopping 11,500 rpm.

The factory team entered two 155 V6 TIs piloted by Alessandro Nannini and Nicola Larini. The 1993 season was dominated by Larini winning 11 of 22 races, and Alfa secured many victories in the next season.

Of course, Alfa did have extensive experience in touring cars before the 155, as the next podium with two Giulia GTA illustrates.

The Alfa Romeo GTA variants won the European Touring Car Championship (ETCC) in 1966, 1967, 1969 1971 and 1972. The GTAs were also successful overseas, winning the Sports Car Club of America’s Trans-Am championship in 1966.

The remaining cars were from the already mentioned Tipo 33 series developed by Alfa Romeos factory team Autodelta. The team was managed by Carlo Chiti. Who worked for the pre-war factory team Alfa Romeo and this with Enzo Ferrari.

The Tipo 33 was developed to challenge the Porsche 904, and entered World Sportscar Championship from 1967 to 1977, winning the championship title in 1975 and 1977. The company developed a Group C prototype in the early 1990s, which is currently showcased in Sinsheim at the Mythos Alfa exhibition.

Sinsheim is one of the best places to celebrate Alfa’s 110th birthday

The Velocity theme leads to a cooling-off segment with a corridor showcasing some recent models, like a 156 touring car or a Brera Spyder.

Alfa Romeo’s factory museum proved to be one of my new favourite car museums. It is tough to nominate a single site as “the” best as a national museum, a private collection or a factory museum might choose different paths to the visitors’ heart.

For me, the Museo Storico definitely proved to be one of the best factory museums of the world, that unites a long and glorious history with brilliant Italian styling.

The Alfa Museum’s impressive architecture follows a clear and expressive choreography that adapts the moods of the decoration to the concrete thematic. This guarantees fresh impulses to maintain our attention through the entire exhibition.

FOR AN OVERVIEW OF ALL THE CAR MUSEUMS I EVER VISITED, CHECK OUT THE INTERACTIVE MAP: